From International Affairs Magazine: "The Creation of Ukraine and the Structural Role of Ukrainian Nationalism/Nazism"

Yes, its composed by academics but not too long.

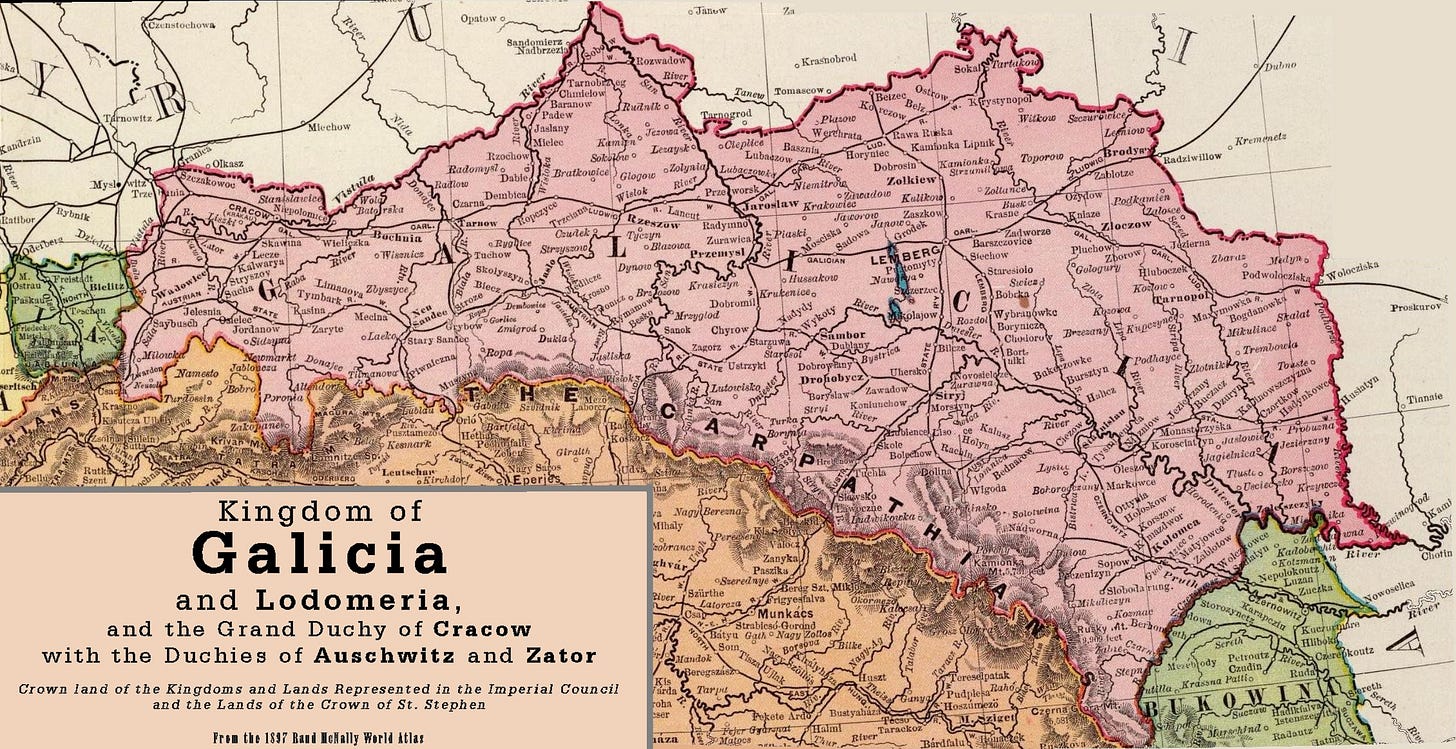

From the 1897 Rand McNally World Atlas

Our two authors:

Eduard Popov, Director of the Center for Public and Information Cooperation "Europe", Doctor of Philosophy and Kirill Shevchenko, Professor of the Minsk Branch of the Russian State Social University, Doctor of Historical Sciences.

I’ve provided several articles on this topic since the SMO began all of them informative in their own way—Putin, Lavrov, Medvedev, Zakharova, and others have all provided their input along with other authors who’ve investigated the Outlaw US Empire’s role in perpetuating Nazism in Ukraine. And thirty years ago, I read the translation of Hrushevsky’s history just after the USSR’s dissolution and Ukraine’s declaration of independence; it was quite a convoluted mess that discussed peoples and places I’d never heard of before within Eastern Central Europe. The paper’s title, "The Creation of Ukraine and the Structural Role of Ukrainian Nationalism/Nazism" and its contents in Russian can be found here. Its translation follows:

Eastern Galicia, traditionally considered a bastion of Ukrainian nationalism, finally acquired such an ethno-cultural appearance only after the genocide of Galician-Russian activists unleashed by the Austro-Hungarian authorities during the First World War. Even in the first quarter of the 20th century, Ukrainian identity was not yet fully established among the Galician-Russian population of Galicia. And among the Galician-Russian intelligentsia, there was a widespread view of the local Rusyns as an integral part of the triune Russian people "from the Carpathians to Kamchatka."

At the beginning of the 20th century, in Austrian Lviv and in the 1920s and 1930s, newspapers in Russian were published in Polish Lviv, defending the idea of all-Russian unity of Great Russians and Little Russians and polemicizing with Ukrainian nationalists. "The Russian-People's Party in Galicia professes... national and cultural unity of the entire Russian people, and therefore recognizes as its own the fruits of the thousand-year cultural work of the entire Russian people, taking into account the belonging of the Russian population of Galicia to the Little Russian tribe of the Russian people"1 - declared the congress of the Russian-People's Party of Galicia, held on January 27 (February 7), 1900 in Lvov. At the beginning of the 20th century, public figures of Galicia noted the wide spread of spontaneous "Muscophile" sentiments among the "Russian common people of Galicia"2, pointing out that the Galicians are superior to "the Little Russian and Great Russian common people in Russia in the development of national consciousness, in patriotism and in deep attachment to the Russian rite and to the church"3. It is noteworthy that activists of the Ukrainian movement were forced to admit this, expressing regret that the Galician peasants were "naturally Muscophiles"4.

Social engineering of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation of the Ukrainian project

Radical Ukrainian nationalism is a new ethno-cultural image of the ancient long-suffering Galicia, raped and disfigured during the bloody Austro-Hungarian terror during the Great War of 1914-1918. Centuries earlier, Galician Rus remained the cornerstone of the all-Russian ideology, giving rise to a huge number of thinkers who substantiated the idea of all-Russian unity, and martyrs who laid down their lives in the struggle for these ideals. The aggressiveness, cruelty, cave narrow-mindedness and acute intellectual insufficiency of Ukrainian nationalists are a vivid manifestation of the "neophyte complex" well known to psychologists.

It is the neophyte converts who are inclined to extreme, sometimes fanatical forms of proving their devotion to some new faith or idea they have adopted, which for the Galician neophytes became the primitive and artificial dogmas of Ukrainian nationalism. As noted by the American researcher J. Armstrong, Ukrainian nationalism differs from other varieties of "integral nationalisms" by a greater degree of totalitarianism, irrational mysticism, an exaggerated cult of violence, war and terror, as well as a tendency to the imaginary and far-fetched5.

A prominent representative of the Galician-Russian movement, O.A. Monchalovsky, as early as 1904, gave a damning assessment of Ukrainian nationalism, describing it as "a retreat from the centuries-old language and culture developed by all branches of the Russian people, self-transformation into an inter-tribal rag, into a wipe of Polish and German boots... renunciation of the primordial principles of his people"6. It is indicative that the Ukrainian movement was assessed in a similar way by the prominent Czech politician and public figure K. Kramář, who stressed that in Austria-Hungary Ukrainian politicians from Galicia acted as an obedient tool of Vienna and Berlin7.

Galician-Russian thinkers proceeded from the primordial unity of all Russian lands. As patriots of Galicia, the Galician-Russian figures emphasized the colossal role of the Galicians in the all-Russian history, noting that the natives of Galician Rus made a great contribution to the rise of the Moscow principality during the period of feudal fragmentation and the Mongol-Tatar yoke. Among the most famous of them was Metropolitan Peter, a native of Galicia, who, supporting the unification policy of the Moscow prince Ivan Kalita in the second quarter of the fourteenth century, transferred the metropolitan throne to Moscow, making Moscow the spiritual center of Russia.

Describing the position of Galician Rus as part of Poland, which seized the Galician lands in the 1340s, the Galician-Russian leaders emphasized that the policy of the Polish kings was aimed at "breaking and destroying the connection between the Russian subjects of Poland and the Russian inhabitants of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, which was emerging at that time in the north, especially since the Russian subjects of Poland did not differ in faith, language and writing from the Russian inhabitants of the Moscow principality... For the same purposes, the church union concluded in Brest was used8.

The beginning of the national revival in Ugric and Galician Rus in the first third of the 19th century was determined by the activities of convinced supporters of all-Russian unity. D.I. Zubritsky, whose name is associated with the first manifestations of the national revival of the Galician Rusyns, was rightfully considered the leader of the "Russian" direction, maintained contacts with the professor of the Moscow University, the famous historian M.P. Pogodin and was a convinced supporter of the Russian literary language as the language of "culture and science in Galicia"9. In his letter to the famous Czech national figure V. Hanka on December 27, 1852 (January 8, 1853), D.I. Zubritsky quite definitely spoke in favor of the Russian literary language for all branches of the Russian people. "Just as the Germans in Strasbourg, in Dorpat, in Surich and Hamburg write only dialects and understand each other, so the Russians must write in only one dialect, already firmly founded and elegantly processed"10, - D.I. Zubritsky stated in his letter to V. Ganke, referring to the Russian literary language. The desire to adopt the Russian literary language by the Galician-Russian intelligentsia, however, was not something unique at that time, since similar ideas, in particular the idea of the Russian language as the common literary language of all Slavs, were expressed by representatives of other Slavic peoples, including Croats, Slovaks and Czechs11.

In addition to D.I. Zubritsky, the initial stage of the national revival in Galicia was associated with the names of M. Shashkevich, I. Vagilevich and Y. Golovatsky, who went down in the history of Galician Rus under the name of the "Russian Trinity". Published in 1837 by the "Russian Trinity", the literary almanac "Mermaid of the Dniester", which became "the most important milestone in the history of the national revival of Galicia", convincingly demonstrated clear all-Russian motifs. For example, in the poem "Memories" by M. Shashkevich published there, the plots of all-Russian history were glorified, including the golden era of Yaroslav the Wise, as well as the power and glory of Novgorod. It is noteworthy that the content of the "Mermaid of the Dniester" was not to the taste of vigilant Austrian officials. As a result, in Galicia, the almanac was banned and confiscated by the police, and its authors were expelled from the Lviv Theological Seminary as punishment12. Thus, the first manifestations of the cultural and national activity of the Rusyns of Galicia in the 1830s directly testified to their awareness of the historical and spiritual unity of the Russian lands and their desire to build their cultural work on this basis.

During the revolution of 1848, the Austrian administration was forced to rely on the nascent national movement of the Rusyns of Galicia in order to counteract the revolutionary movement of the Galician Poles. At that time, the Austrian authorities revealed their desire to oppose the all-Russian identity of the Galician Rusyns in every possible way, contributing to the formation of a special self-consciousness among them.

Vienna's flirtations with the Rusyns, caused by the tactical goals of Austrian policy in the conditions of revolutionary upheavals, contributed to a noticeable revival of the national activity of the Galician Rusyns, expressed in the appearance of the Galician-Russian press and a number of national organizations. In particular, during the revolution of 1848-1849, the People's House and the Galician-Russian Matica were founded in Lviv, which "along with the Stavropegian Institute, became the cultural centers of the Russian movement for almost a century..."13. Although after the suppression of the revolution of 1848, Vienna returned to an alliance with the Polish nobility of Galicia, the Galician-Russian cultural and educational organizations created during the revolution survived, subsequently playing an important role in the development of the Russian movement in Galicia. At the congress of the Galician-Russian intelligentsia in Lviv in 1848, it was decided to contribute to the purification of the "Galician-Russian dialect" from Polonisms and its rapprochement with the Russian literary language.

As for the Ukrainian movement in Galicia, in the opinion of Galician-Russian figures, such activities received a colossal impetus in connection with the preparation of the Polish uprising of 1863. Polish politicians, having by this time become convinced of the counterproductive course aimed at Polonization of the Galician Rusyns and their inclusion in the Polish people, made attempts to turn the Rusyns of Galicia into an instrument of struggle against Russia. "In the early 1860s, preparations were underway for the Polish uprising of 1863. Polish agents, who wanted to draw the Galician-Russian youth into the uprising, began to diligently spread the idea of Little Russian separatism among them," wrote O.A. Monchalovsky. - For this purpose, "Dziennik Literacki" and other Polish publications published Little Russian poems that breathed hatred for "Moskwie", that is, for Russia, and expressed regret for the fate of the unfortunate "Ukraine-Rus"...

The Ukrainophile movement strengthened significantly after the uprising of 1863. Crowds of Polish emigrants from Russia poured into Galicia, and remarkably, they all turned out to be ardent Ukrainophiles."14. The Polish administration of Galicia actively promoted the employment of Polish emigrants-Ukrainophiles in local public, scientific and educational institutions, where they tried to influence the mindset of young Galicians. In particular, at this time, the opinion of F. Dukhinsky about the fundamental difference between Southern and Northern Russia and that for the "liberation" of the Little Russians needed an alliance with the Poles began to spread.

It is noteworthy that Dukhnovych, Dobryansky, Pavlovich and other figures of the Ugric Rusyns reacted extremely negatively to the attempts to reform the Galician-Russian writing and create a Ukrainian literary language, perceiving it as dangerous separatism. For example, A. Dobryansky considered the appearance of a separate literary language among the Little Russians to be a "treacherous betrayal" not only of the Russian people, but also of the entire Greco-Slavic world.

Over time, the Ukrainian orientation in Galicia strengthened, which contributed to an increase in the cultural gap between the intelligentsia of the Galician and Carpathian Rusyns. It is noteworthy that the attempts of Ukrainian leaders V. Hnatyuk and M. Drahomanov to establish contacts with the "brothers" south of the Carpathians at the end of the 19th century ended in a disappointing embarrassment for them. Ukrainian activists complained about the sharply negative attitude towards them on the part of the Carpathian Rusyns15.

With the invention of the Ukrainian phonetic writing by P. Kulish (the so-called "kulishivka"), created in opposition to the Russian etymological writing, the Austro-Polish ethno-cultural technologists received a new effective tool for separating the Galician-Russian writing from the Russian literary language and a means of influencing the self-consciousness of the local population. It is known that P. Kulish himself reacted extremely negatively to the use of the phonetic alphabet created by the Poles to deepen the cultural and linguistic split between the Little Russians and the Great Russians. In his letter to the famous Galician-Russian figure B. Deditzky in 1867, Kulish frankly stated that "seeing this banner (kulishivka) in the hands of the enemy, I will be the first to strike it and renounce my spelling in the name of Russian unity."16.

Nevertheless, the Polish managers of the "Ukrainian project" in Galicia sought to take advantage not only of the Ukrainian phonetic alphabet invented by Kulish, but also of Kulish himself as an authoritative figure of the Ukrainian movement in Russia. In an effort to turn Eastern Galicia into the center of the Ukrainian national movement, transforming it from a cultural and linguistic into a political project, the Polish elite of Galicia offered Kulish to head the publication of the Ukrainian press in Galicia.

Describing the state of Polish society in Eastern Galicia in the second half of the 19th century, A.I. Dobriansky aptly noted that "all Polish officials, professors, teachers, even priests began to study philology, not Masurian or Polish - no, but exclusively Russian, in order to create a new Russian-Polish language with the assistance of our traitors, from which the transition to purely Polish would no longer present any difficulties."17.

Neither the creator of the Ukrainian phonetic alphabet P. Kulish, nor the well-known historian M. Kostomarov, who stood at the origins of the initial, cultural phase of the Ukrainian movement, wanted to transfer it to the political plane and break with the idea of all-Russian unity. However, what N. Kostomarov and P. Kulish refused to do, M. Hrushevsky would later do, whose historical works would be called upon to substantiate the deep civilizational differences between Southern and Northern Russia.

The agreement between the Ukrainophile part of the Galicians and the Poles, known as the "New Era", was marked by an intensification of the civilizational split between the Russian Galicians and Ukrainophiles, who relied on the support of Vienna and the Galician Poles. As a result, the previously united "Russian Club" in the Galician Sejm split; "in the whole of Galicia, a fierce struggle of parties ensued... At the same time, there was a persecution of all those who turned out to be opponents of the "program"18.

The proclamation of the "New Era" became an ideological preparation for an attack on the Russian Galicians and the Russian literary language in Galicia. Since 1892, phonetic spelling ("kulishivka") was introduced in the schools of Galicia instead of the etymological script traditional for Rusyns and accepted in pre-revolutionary Russia, thanks to which Rusyns could freely read books published in Russia. However, the introduction of phonetic spelling in Galicia faced considerable difficulties. For example, in February 1893, the organ of the Galician-Russian intelligentsia, the Lviv "Galichanin", ironically reported that the organ of the Galician Ukrainophiles, the newspaper "Dilo", sharply criticizing the supporters of traditional etymological spelling and advocating phonetics, nevertheless "uses etymological spelling in its columns"19.

The official introduction of phonetics marked the beginning of a campaign of persecution of the Russian literary language. Thus, "students of the Lviv Theological Seminary were forbidden to study with it, books written in the Russian literary language began to be taken away from students, the societies of students "Bukovyna" in Chernivtsi and the "Academic Circle" in Lviv were closed..."20. Since the 1890s, the distortion of history by Ukrainian figures in Galicia has intensified, covering the entire public sphere from education to the press.

The Emergence of "Organized" Ukrainian Nationalism/Nazism: Austro-Hungarian Roots and Modern Shoots

The problems of modern Ukrainian nationalism / Nazism in domestic historiography are extremely poorly developed. One of the few examples was an article by E.A. Popov devoted to the analysis of ideological, political and geographical differences in modern Ukrainian nationalism, published in 2010 in the RISS journal "Problems of National Strategy"21.

The history of institutionalized Ukrainian nationalism dates back to 1929, when the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was created. After the murder of its leader Yevhen Konovalets by Pavlo Sudoplatov, the organization split (in 1940) into the warring Bandera and Melnikov factions (OUN-b, or OUN-r (revolutionary), and OUN-m).

In July 1919, Eastern Galicia and Western Volhynia became part of the Polish state, which became objects of Polonization. Hence the radical anti-Polish orientation of the OUN, hence the pro-German geopolitical and pro-Nazi ideological orientation of the OUN during the time of E. Konovalets and both factions of the OUN after the split. Even before Hitler came to power, close ties were established between Ukrainian nationalists and the NSDAP; OUN activists studied in the party schools of the German Nazis. Subsequently, the intelligence services of Nazi Germany took patronage over the OUN factions: the Abwehr military intelligence - over the OUN-b, the SD (SS Security Service) - over the Melnikovites. Thus, the commander of the OUN-UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army), the military wing of the OUN-b, R. Shukhevych had the rank of Hauptmann of the Abwehr and was the deputy commander of the punitive and sabotage unit "Nachtigall" created by the Nazis in occupied Poland.

A number of ideologists and leaders of the OUN openly called Ukrainian nationalism part of the European fascist movement. It is important to note that the OUN gravitated not towards Italian fascism (the doctrine of the corporate state), but towards German National Socialism with its racial theory. Therefore, the OUN, like the Croatian Ustasha, is a version of National Socialism with its genocidal practices of solving the national question. Ukrainian nationalists did not have their own state, and their social support was made up of illiterate villagers, and many leaders were the sons of Greek-Uniate priests. Galicia and Volhynia, the two centers of Ukrainian nationalism, were backward agrarian regions. In more urbanized Galicia, the upper levels of the social and cultural hierarchy were occupied by Poles and Jews. Thus, Ukrainian nationalism, which developed in imitation of German National Socialism, arose in a culturally backward and agrarian environment and served as the ideological and political basis for ethnic revenge.

The OUN combined territorial expansion with the issue of ethnic "purity." All peoples were divided into "friendly" and "unfriendly". The former were to be evicted from the territory of Ukraine, the latter were subjected to theoretically and programmatically justified violent acts.

On June 30, 1941, the day after the Red Army left Lviv, the Bandera followers proclaimed the Ukrainian State under the leadership of Yaroslav Stetsko. Close cooperation with Adolf Hitler's Greater Germany was proclaimed. After that, the first punitive action began to implement the OUN-r program in the field of national policy: the extermination of the Polish and Jewish population of Lviv.

At the third conference of the OUN-b in February 1943, it was decided

to create the UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) led by Roman Shukhevych and radically solve the Polish question. Thus, the Volyn massacre was launched - the destruction of the Polish population of the region. In 2016, the Sejm and the Senate of Poland recognized the Volyn massacre as an act of genocide of the Polish people. In total, during the Volyn massacre, which was carried out by both factions of the OUN and the "Polissia Sich" of Bulba-Borovets, from 30 to 60 thousand Poles were killed. The total number of Polish victims of Ukrainian nationalists in Galicia and Volhynia alone is up to 200 thousand. In addition, Ukrainian nationalists, as part of punitive units in the service of the Wehrmacht and police formations of the SD, participated in the destruction of hundreds of Belarusian villages and towns. The burning together with the inhabitants of the Belarusian village of Khatyn is the work of Ukrainian nationalists from the OUN-m.At the end of the war and immediately after its end, many OUN-b and OUN-m militants and activists took refuge from retribution in the United States and Canada. This was impossible without the support and direct sanction of the state authorities - the United States and Great Britain. And after the collapse of the USSR, the ruling circles of the United States carried out the reverse export of Nazi personnel and technologies to Ukraine and ensured their introduction into the scientific and educational sphere. At the same time, the party structures of the Bandera and Melnikovites were recreated.

Thus, modern Ukrainian Nazism leads ideological and organizational continuity from Hitler's collaborators during World War II, the executioners of Volyn and Khatyn.

Let us briefly enumerate the organizational structures of the successor organizations of the OUN-b and OUN-m in post-Soviet Ukraine. Let's call them "old nationalists".

This generation/direction is represented by two groups of parties - parliamentary and direct action. The parliamentary type includes:

- Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) - (Bandera or "revolutionary" wing);

- Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (once part of the Our Ukraine electoral bloc). This party for entry into parliament was created on the basis of the OUN;

- Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) - faction of A. Melnyk;

- The All-Ukrainian organization "Svoboda", whose program is based on the principle of "national democracy", that is, democracy only for Ukrainians.

Parties and organizations of the direct action type include:

- The political party "Ukrainian National Assembly" (UNA) after the departure of its charismatic leader D. Korchinsky, which has a paramilitary wing called "Ukrainian National Self-Defense" (UNSO). Then the UNA-UNSO was fragmented into a number of organizations. It has long lacked the strength it boasted of in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The role of the UNA-UNSO is also characterized by the fact that in the 1990s and early 2000s it served as an instrument of external expansion and performed the tasks of the military intelligence of Ukraine (GUR MO) - what is now called a proxy force. This was the case during the Transnistrian conflict. But the external activity of the UNA-UNSO was most clearly manifested in anti-Russian actions: the war in Abkhazia on the side of Georgia, two Chechen wars, the conflict in South Ossetia.

The participation of UNA-UNSO militants, a proxy force of Ukrainian military intelligence, in two military conflicts on the territory of Russia (the Chechen Republic), their participation (along with Ukrainian special forces and other military specialists) in Georgia's attack on Russian peacekeepers in August 2008 allows us to place a different emphasis in Russian-Ukrainian relations. Ukraine has participated in the invasion of Russian territory and in acts of aggression against Russian servicemen - fighters of the peacekeeping battalion in Tskhinval - at least three times.

- The Social-Nationalist Party of Ukraine, from which the All-Ukrainian Organization "Svoboda" (leader O. Tyahnybok), the Youth Nationalist Congress, and a number of other organizations left.

- The public organization "Stepan Bandera Trident", which was founded on the initiative of the OUN-r and was known as the most radical nationalist force in the 1990s - 2000s. It was from Tryzub that Dmytro Yarosh, the self-proclaimed leader of the Right Sector, an association of Ukrainian Euromaidan nationalists, came out. It should be noted that the ideological development of Trident stopped at the level of the 1940s, which became the subject of sarcastic and mocking remarks from their competitors from among the "new right";

The program of "Tryzub" interprets the ideal and priorities of the national state as follows: "Our highest national duty is the cultivation and implementation of the Ukrainian national idea - the idea of state self-assertion of the Ukrainian nation, the creation of a Ukrainian national state with national power and a functioning system of Ukrainian national democracy"22.

Various structures of the "old nationalists" advocate the redrawing of existing borders and the "return" of lands with a Ukrainian ethnic population to Ukraine. Ukrainian nationalists have territorial claims to all of Ukraine's neighbors, including Ukraine's main ally and lobbyist in the EU, Poland (the historical lands of Ancient Rus - Podlachia, Kholmshchyna, Lemkivshchyna, etc.). But the most large-scale territorial claims are against Russia: the territory of the Lower Don (or the entire Don), the "Ukrainian" Kuban (in 1792, the Russian Empress Catherine the Great endowed the Cossacks of the Loyal Black Sea Army, whom Ukrainian propaganda considers Ukrainians, with lands in the Kuban conquered from the Ottoman Empire). The old slogan - to return the lands "from Sana'a to the Don", which was included in the anthem of Ukraine, is shared by all factions of Ukrainian nationalists. However, some go even further in their territorial claims and demand the "return" to Ukraine of the lands of the so-called Gray and Green Wedges - the territories of settlement of migrants from the Little Russian provinces of the Russian Empire in Southwestern Siberia and the Far East.

The New Right, another generation/direction of Ukrainian nationalism/Nazism, is represented by the following structures:

- D. Korchinsky's organizations: in the 1990s - UNA-UNSO, in the 2000s - "Brotherhood";

- Kharkiv organization "Patriot of Ukraine" - the paramilitary wing of the Social National Assembly (spelling as in the original), as well as a number of ideologically close organizations.

The pen test of the combat detachments of Ukrainian nationalists took place during numerous protests. The most ambitious of them are "Kuchma Get" and, of course, the first "Orange Revolution"23. During the period of the so-called Euromaidan, a number of organizations close to the Patriot of Ukraine emerged and became active, which can be attributed to the racist camp rather than to traditional Ukrainian nationalists (White Hammer, etc.).

The geographical (civilizational) aspect of Ukrainian nationalism deserves special consideration. Lviv, the "Piedmont of Ukrainian nationalism," was also the intellectual center of the "old nationalism." However, the demographic, economic and intellectual resources of Galicia could not be compared with the capabilities of Russians in terms of language and culture in the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine - the historical Slobozhanshchina (part of the Moscow (Russian) state since 1500) and Novorossiya (annexed to the Russian Empire after the victories of the Russian Imperial Army during the 18th century). In the new historical conditions, the dispute between the "Banderites" and the "Petliuraites" - Western and Eastern Ukrainian nationalists - was revived. In the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine, historical Novorossiya, the socio-cultural environment was different: a developed and educated urban population, the largest megalopolises arose and developed rapidly: Kharkov, Donetsk, Odessa. Kiev, which is Russian in language and culture, should also be included there.

The most interesting example is the public organization "Patriot of Ukraine", created in Kharkiv in 2005. Kharkiv, the first capital of Soviet Ukraine, has always had a special status, it is the second most populous city in Ukraine and its scientific capital. Special literature was prepared for the "Patriot of Ukraine" in Russian, the working language of the organization was Russian. Patriot of Ukraine is a movement that consistently develops a racist and pan-East Slavic (with a strong admixture of paganism) rather than a Ukrainian ethnic line. "Nation (sic. - Author) - approves the program document of the organization - has the right to improve its own health through the approval of racial, eugenic and economic legislation"24.

The leader of the "Patriot of Ukraine" - Andriy Biletsky, a historian by education, in the Nazi environment is called the honorary nickname "White Leader". Biletsky and the main ideologist of the "Patriot of Ukraine", historian O. Odnorozhenko were arrested during the presidential rule of V. Yanukovych and released after the victory of the Euromaidan. After being released from prison, Biletsky immediately became actively involved in military, political and social activities. The fruit of this activity was the creation of a battalion, then the Azov regiment - one of the most combat-ready (primarily in terms of motivation) units of the Ukrainian army / National Guard and a center of attraction for neo-Nazis around the world.

We are more interested in the political and social initiatives of A. Biletsky and the social-nationalists.

In October 2016, the National Corps political party was created on the basis of the Azov regiment. The leader of the party is A. Biletsky.

The main areas of non-political activity of the structures created on the basis of the Azov Regiment:

1) Work with children and youth by organizing camps for military-patriotic training. This is perhaps the main area of activity of Azov's civil structures.

2) Assistance to needy citizens in solving their housing and social problems (illegal construction, assistance to trade unions, etc.).

3) Raids against drug dealers.

4) Fight against ethnic crime.

5) Establishing contacts with representatives of foreign (primarily American) special services and officers from the armies of NATO countries operating in Ukraine, as well as numerous mercenaries and volunteers from neo-Nazi circles in Europe and Western countries. The goal is to create and strengthen foreign relations with an eye to the future.

Thus, the National Corps and other structures of Azov are trying to overcome the narrow framework of the nationalist electorate and enlist the support of broad segments of the population. At the same time, they are establishing close ties in military circles (active and very successful propaganda in the officer corps of Ukraine) and effective international work (the neo-Nazi "international", military circles and special services of the United States and NATO countries)25.

Ideologically, the "new right" is a qualitatively different force from the "old nationalists." Social-nationalists directly appeal to the prototype - German National Socialism, and not to its mossy Ukrainian epigones - Bandera, Melnikovites, etc. The intellectual "library" of these structures also includes the achievements of modern Western neo-Nazis and racists. The social-nationalists, however, did not break with the old symbols, accepted the "heroes" of the OUN-UPA into their pantheon - the "nation" needs its own "heroes". But the main nerve is the imitation of German National Socialism and its development, the main character is Hitler, not Bandera.

The geopolitical aspirations of the Ukrainian social-nationalists look an order of magnitude larger, and the horizon of thinking is wider than the provincial imperialism of the "old" nationalists of Galicia. They dream of a "great Ukraine" "from Sana'a to the Don" (or to the Caspian Sea), that is, of redrawing borders in Europe, including at the expense of Poland's "ally". The plans of the social-nationalists are much more ambitious: the creation of a Central European confederation (under the auspices of Ukraine, of course) from racially pure states with an eye to Western Europe26. This new force will exercise control over all of Eurasia, and therefore over the world. This is nothing more than the return of Adolf Hitler's geopolitical aspirations from political oblivion.

So, the "old nationalists" have a Great Ukraine for Ukrainians. The "new right" has a Great White Eurasia under the rule of the White Leader.

In Russia and the world, they do not understand the nature of modern Ukrainian Nazism at all. In the world (in the West) they prefer not to notice it, any reasoning on this topic is explained by "Russian propaganda". In Russia, they are fighting old phantoms, still seeing modern Ukrainian Nazism as "Banderites". The latter did not disappear, but ceded the palm to a more dynamic and powerful force - the new Nazism, which grew up in the urban centers of the east and south of present-day Ukraine, with Russian urban culture and the ability to think on a planetary and cosmic scale.

This explains why Ukraine has become a mecca for European and all world neo-Nazis. The "old nationalists" with their wretched cult of political losers Bandera and Shukhevych could not interest neo-Nazis in Europe or North America. The structures that grew out of the Kharkiv "Patriot of Ukraine" are a completely different matter. The ideas of white racism, a kind of racist globalism, the rejection of narrow ethnic boundaries (ideological neo-Nazis from the Russian Federation are also fighting in Azov), a very modernist ideology aimed at the future, and finally, the charismatic figure of the White Leader Biletsky - all this taken together predetermined the popularity of Azov and its subsidiaries among racists and neo-Nazis in the world.

1Monchalovskiy O.A. The main foundations of the Russian nationality. Lvov: Tipografiya Stavropigiiskogo instituta, 1904. Pp. 17-18.

2Monchalovskiy O.A. Literary and political Ukrainophilism. Lvov: Tipografiya Stavropigiyskogo instituta, 1898. P. 187.

3Ibidem.

4Ibidem. P. 185.

5See: Armstrong John A. Ukrainian Nationalism. Third Edition. Englewood, Colorado. 1990. P. 14.

6Monchalovskiy O.A. The main basics...

7Kramář K. In defense of the Slavic policy. Prague - Paris, 1927. P. 14.

8Monchalovskiy O.A. Holy Russia. Lvov: Tipografiya Stavropegiyskogo instituta, 1903. P. 47.

9Pashayeva N.M. Essays on the History of the Russian Movement in Galicia of the XIX-XX Centuries. Moscow: Imperial Tradition, 2007. P. 39.

10Letters to Vyacheslav Ganka from the Slavic lands. Published by V.A. Frantsev. Warsaw: Printing House of the Warsaw Educational District. 1905. P. 389.

11Daniš M., Matula V. M.F.Rajevskij a Slováci v 19 storočí. Bratislava. 2014. S. 14.

12MonchalovskI O.A. Holy Russia... P. 87.

13Pashayeva N.M. Edict. cit., p. 34.

14Monchalovskiy O.A. Literary and... Pp. 71, 74.

15See: Magocsi P.R. The Shaping of a National Identity. Subcarpathian Rus, 1848-1948. Harvard University Press. 1978. P. 60-63.

16Monchalovskiy O.A. Literary and... P. 78.

17Dobryansky A.I. On the Current Religious-Political Situation in Austro-Ugric Russia. Moscow, P.V. Levdik Publ., 1885. P. 12.

18 Ibidem.

19Galichanin (newspaper). Lviv. 4 (16) fierce 1893. Part 25.

20Pashayeva N.M. Edict. cit., p. 81.

21Popov E.A. New Trends in Modern Ukrainian Nationalism // Problems of National Strategy. 2010. №3.

22National Power: All-Ukrainian Organization "Tryzub imeni Stepan Banderi". Program for the Realization of the Ukrainian National Idea in the Process of State Creation // http://banderivets.org.ua/index.php?page=pages/zmist4/zmist402

23Cm. Popov E.A. Ukrainian NGOs: from the "orange revolution" to the export of "democracy" to the post-Soviet countries // Orange networks: from Belgrade to Bishkek (edited by N.A. Narochnitskaya). St. Petersburg: Aletheia, Istoricheskaya kniga, 2008.

24NATIONAL LAW. Draft program of the VGO "Patriot of Ukraine" // http://www.patriotukr.org.ua/index.php?rub=doc (Archive).

25For more details see: Popov E.A. Postmaidan Ukraine: From the Cult of New Historical Heroes to the Change of the Civilizational Matrix // History as a Tool of Geopolitics: International Scientific and Practical Conference. Institute of Political Studies of the Academy of Sciences of Serbia. Belgrade, 13-14 March 2022 Beograd, Institute for Political Studies, 2022 (in Serbian) // www.ips.ac.rs

26NATIONAL LAW. The draft program of the VGO "Patriot of Ukraine"...

Interesting that little reference was made to religion while the emphasis was on language as the controlling factor at the outset of this plague, or perhaps the religious component is too contextually imbedded in the historian authors. And it’s always about exclusive lands for themselves. Safe to say it all began with divide and rule to capture or continue holding certain lands. The old ploys are presently being used and it’s the serfs who suffer as usual.

*

*

*

Like what you’ve been reading at Karlof1’s Substack? Then please consider subscribing and choosing to make a monthly/yearly pledge to enable my efforts in this challenging realm. Thank You!

Interesting article, I was not aware that their was a pro Russian elite in the Galicia back in the the 19th Century. So the Ukrainian language is basically a construct of Austrian Imperialism. I still believe that Russia will be forced to occupy all of modern Ukraine and incorporate it into Ukraine to exterminate this vile and perverted ideology. A great book to recommend about the fraudelent identity of the modern Ukrainian state is "Heroes and Villains" by the Canadian historian David R. Marples written in 2007 after the Orange Revolution.

I admire you for finding all this information, and thank you for your work. I'am browsing trough Russian publications on a regular base, but there is a lot that escapes my attention. And then there is your substack, my newest go-to-page!

I recently discovered that the first concentration camps on European soil were created by the Austro-Hungarians in 1914. The targeted ethic group were the "Carpatho-Rusyns". Russian sources talk about a "genocide". https://dzen.ru/a/XUYO_vjqZwCt6boP Геноцид русин в Австро-Венгрии: как это было | Русская Семёрка | Дзен

For more information, see also:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thalerhof_internment_camp